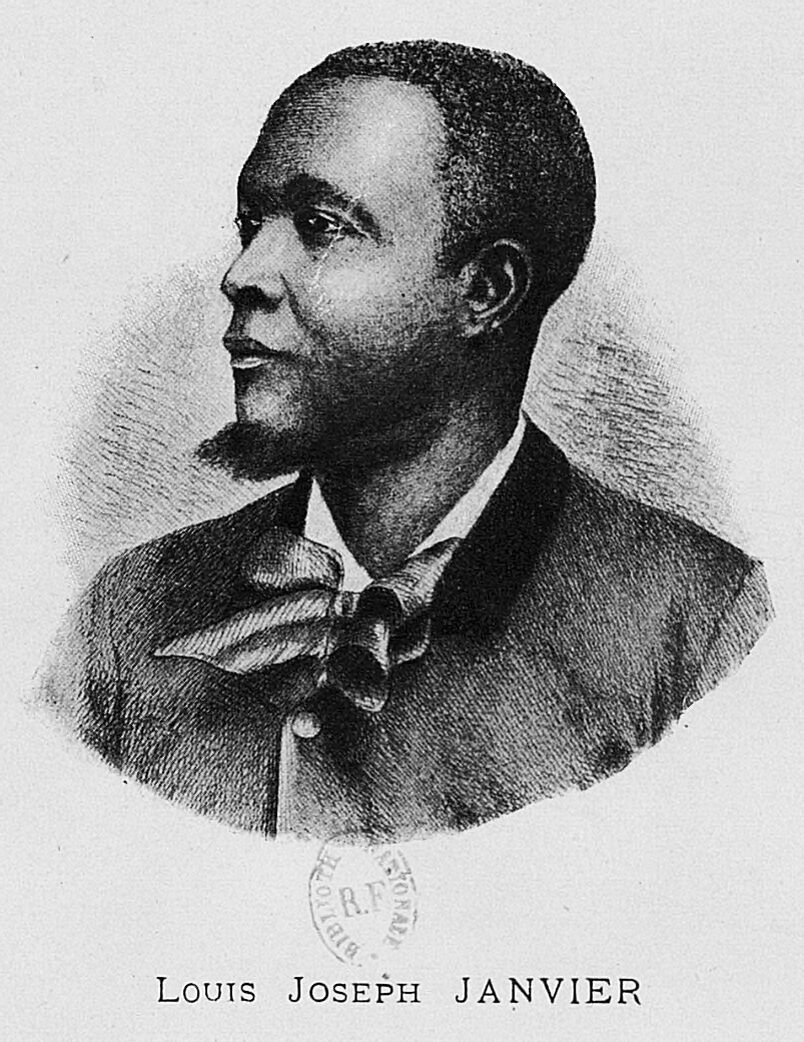

In light of the recent political and social unrest in Haiti, the reflections of earlier thinkers retain a striking relevance. One such figure, Louis-Joseph Janvier (1855-1911), produced a vast and varied oeuvre encompassing history, constitutional law, diplomacy, fiction, journalism, and political commentary. His works provide an excellent opportunity to explore some of the persistent thorns in the history of the Black Republic: the peasant question, the color question, development, and forging a strong nation-state. Although Janvier’s views of development and his vision for Haiti are more applicable to the time of bayonets rather than today, one cannot help but sense a parallel between the Haiti of today and the Haiti in the turbulent years leading to the first US Occupation. While the UN’s MINUSTAH occupation has ended in name, it seems that the nation will continue in his phase of recurring instability for the foreseeable future. Perhaps it may take the form of another MINUSTAH (or more recently the MINUJUSTH), but these uncertain times call for those interested in Haiti’s future to contemplate its past. Thus, Janvier remains relevant in the 21st century. And far more than a noirist, as he is often depicted, Janvier’s nuanced approach to race, class, and development deserve our scrutiny.

Janvier’s Views on the Fundamental Question of Land

First, Janvier is important among 19th century Haitian writers for his explanation of Haiti’s problems through class lens. Identified by Jean-Jacques Cadet as a Haitian intellectual influenced by socialism and Marxism, Janvier attributes the problems of Haiti to class war, a rural proletariat versus the owners of large estates, grand proprietors (Les Constitutions d’Haïti, 483). According to Janvier’s view of Haitian history, the assassination of Dessalines in 1806 prevented a veritable land distribution, leading to Goman’s revolt for land reform in the Sud (Les Constitutions d’Haiti,488). Furthermore, Boyer’s Code Rural was a later attempt to prevent the formation of a class of peasant proprietors, causing a class war (Les Constitutions d’Haiti, 493). Indeed, Janvier compared Boyer’s Code Rural to slavery because of its restrictions on the movements of paysans (Les Constitutions d’Haiti, 149). This unpardonable error of Boyer ensured peasant uprisings of rural proletariats against the bourgeoisie (Les Constitutions d’Haiti, 152).

However, Armand Thoby argued against Janvier’s presentation of the history of land reform in Haiti. For Thoby, a member of the Liberal party, it was under Pétion that smallholder agriculture was constituted (La Question agraire en Haiti, 18). Subsequent scholarship on land reform in Haiti tends to support Thoby’s assertion, although Janvier did recognize Petion’s land distribution policies as limited to a few carreaux for veterans (Les Constitutions d’Haiti, 145). Nevertheless, Janvier’s identification of class and access to land as key to Haitian peasant unrest, and recognition of the class character, was still accurate. As Alex Dupuy explains, rural Haiti in the 19th century was divided into sharecroppers who did not own land, peasants with land titles, ’middle-class peasants” with titles, and a “landed oligarchy” that rented out land or hired those less fortunate as sharecroppers and day laborers (Dupuy, “Class Formation and Underdevelopment in Nineteenth-Century Haiti,” 22).

For Dupuy, Haitian peasants had mostly controlled the means of production by the second-half of the 19th century, even though perhaps only 1/3 had legal titles. This gave peasants some degree of autonomy, and in areas where the landed oligarchy had more control over sharecroppers or workers, the profits accorded to the landed elites were still meager (Dupuy, 22). In this regard, Dupuy’s observation on the limited surplus raised by bourgeois landholders in their exploitation of the peasant echoes Janvier’s comment on the limited accumulation of capital in this dynamic of class relations (Janvier, La Republique d’Haiti et ses visiteurs, 106). Nonetheless, an unequal relationship persisted and the question of access to land, as well as access to education and other economic reforms, ensured struggle over these questions in the future. The specter of Acaau and peasant uprisings haunted Haiti throughout the period of 1843-1915 and the caco uprisings during the US Occupation.

The Haitian Peasant and the Haitian Worker

Janvier’s views of the laboring classes were a combination of paternalism, nationalist pride, and positivist notions of progress. For Janvier, as for many other Haitian writers of his time, such as Beauvais Lespinasse, Firmin, Price, and Delorme, Haiti represented both Africa and la race noir as a civilized polity. Haiti represented black self-capacity to govern. Haiti was, for these writers, a ‘Black France’ in which Africa and her children were to be regenerated, rehabilitated, and prove to Europe racial equality. Indeed, Janvier identified Haiti as an argument, and Haiti’s success was linked to this larger consistent theme of Haitian nationalism’s unversalist implications for people of African origins (La Republique d’Haiti et ses visiteurs, 123). Thus, the Haitian worker and peasant, as the majority of the population, became a necessary focus to defend Haitian autonomy, vindicate the black race, and overcome Haiti’s political and economic discord.

Furthermore, without the Haitian working classes, there would be no Haiti. The peasantry made Haiti possible in the first place: “En Haiti c’est le paysan qui fait vivre tout le monde. Quand il ne travaille pas, quand il ne vend pas, quand il n’a pas d’argent, personne ne travaille, ne vend, n’achète, ne consomme, n’a d’argent” [“In Haiti, it is the peasant who keeps everyone alive. When he does not work, when he does not sell, when he has no money, no one works, sells, buys, consumes, or has money”] (Janvier, Les Affaires d’Haiti, 257). Everything in Haiti depended on the masses, making Janvier’s populist vision’s favorable views of the Haitian peasant and worker a rational focus. The Haitian peasant, in his response to Cochinant’s bad press of Haiti, possessed admirable qualities: disciplined, obedient, fraternal, and gay (Les Affaires d’Haiti, 263). In addition, Janvier predicts the future superiority of the Haitian worker to that of Anglo-Americans because of the former’s Latin blood, which imbues artistic, original, and charming features (La Republique d’Haiti et ses Visiteurs, 93). The Haitian worker was also generous, proud, sweet, likable, and patriotic (La Republique d’Haiti et ses visiteurs, 96). He even claimed the Haitian worker and peasant mostly abstain from alcohol (La Republique d’Haiti et ses visiteurs, 138). Drawing from Montesquieu, Janvier also argued that peasants work harder on their own land, pointing to successful examples in France and Romania (La Republique d’Haiti et ses visiteurs, 587). All these aforementioned traits, albeit exaggerated in some cases, suggest the degree to which Janvier identified peasants, workers, and artisans as key to refutation of racist discourses of the Black Republic.

As a disciple of Pierre Lafitte immersed in Parisian intellectual circles, Janvier’s Francophile orientation and positivist influences nonetheless shaped his views of the Haitian peasant. For instance, in Le vieux Piquet, a short novel of the lodyans genre, Janvier defended piquet uprisings as just, legitimate and sane struggles (Janvier, Le vieux piquet, 4). Piquet uprisings, beginning with Goman, were a response to the defeat of Dessalines’s promise of land for the majority (Le vieux piquet 9). In this sense, the piquets were the true heirs of the Haitian Revolution. There is some moralizing of a paternalist nature in the novel, too. The narrator of the tale, the head of a lakou and former piquet, directs a message on morality to his grandchildren, urging them to spend less time dancing or avoid frivolous spending (Le vieux piquet, 32). The Protestant work ethic of Janvier’s background was likely influencing this passage of the story, which defends piquets struggles for land but expecting peasant behavior to conform to certain standards that he perceived as necessary for social progress. In this sense, piquets were one of the steps in which the peasant could be freed of superstition and enrich the country (Janvier, Les Antinationaux, 97). They, after obtaining control of their lands, would enrich the state through their labor and dedication to the state.

Religion also played a pivotal role. For Janvier, Roman Catholicism was an obstacle to Haitian autonomy and tied to fetishism and fatalism among peasants. Protestant conversion, on the other hand, was associated with moral reform of the popular classes (Les Affaires d’Haiti, 297). Protestantism would, he believed, support private initiative (Les Affaires d’Haiti, 307), another step forward in Haitian civilization. As one would suspect of an intellectual calling for Protestantism or free-thinking in Haiti, Vodou is another problem for the Haitian lower classes. As a positivist, he linked Vodou to fetishism and polytheism in the first stage in Comte’s idea of 3 stages, comparing Vodou to the ancient beliefs of Greece and Rome (Les Constitutions d’Haiti, 282). Using Ancient Egypt as an example, Janvier argued against fetishism as an impediment to advanced civilizations (Les Constitutions d’Haiti, 281). Moreover, the Catholic Church was hardly less superstitious than Vodou in Janvier’s eyes. Like Comte, Janvier saw in fetishism a possible way in which the fetishist could be more amenable to the positive stage. Firmin was likely thinking on similar lines in his description of African religions as practical rationalism (Firmin, The Equality of the Human Races, 342). Within their own internal logic, African ‘fetishism’ observes the world and responds to the results, within the dictates of its internal logic and observation of phenomena. For Comte, fetishism gave us the subjective method of thought (Comte, System of Positive Policy, Volume 2, 73). Comte later argued polytheism may be easier to adapt for positivism because of the Unity or synthesis of various deities into the shared Destiny, combining the former deities with natural laws (Comte, 89). Protestantism, perceived as subjective, intuitive, scientific, and full of initiative, would be better fit for Haiti to reach the positive stage (La Republique d’Haiti et ses visiteurs, 372). Even better, the Protestant wouldn’t waste time on parties and Carnival (Janvier, Haiti aux haitiens, 36).

Unsurprisingly, Janvier, as a Positivist worried about perceptions of Haiti fallen prey to African atavism, pushed for Protestantism and general education. Like Firmin, he utilized a quasi-Lamarckian explanation of Haiti’s progress on the path of civilization to prove the physical perfectibility of the noir (Janvier, Les detracteurs de la race noire et de la Republique d’Haiti, 47). The civilizing mission of Haiti thus improved the Haitian noir physically, culturally, and mentally. Haitian ‘racial’ mixture was also a part of this to Janvier, who claimed the Haitian black is almost always a sacatra (Les detracteurs de la race noire et de la Republique d’Haiti, 34). The Haitian, in Janvier’s mind, was thus Afro-Latin, on the march toward progress, and with land for every peasant, assured to aid the nation on the path to political, economic, and social liberty. In the meantime, he denied the ongoing practice of Vodou, going as far as denying the old African dances were still practiced in Haiti (La Republique d’Haiti et ses visiteurs, 94).

Building on these positivist premises and Janvier’s vision of social and racial progress in Haiti, Part II delves deeper into his concrete proposals for land reform and the practical steps he envisioned to transform Haitian society.

Bibliography

Auguste, Michel Héctor, Sabine Manigat, and Jean L. Dominique. 1986. Haití: la lucha por la democracia : clase obrera, partidos y sindicatos. Puebla, Pue: Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick. In the Shadow of Powers: Dantès Bellegarde in Haitian Social Thought. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International, 1985.

Bonneau, Alexandre. Haïti: Ses progrès, son avenir; avec un précis historique sur ses constitutions, le texte de la constitution actuellement en vigueur, et une bibliographie d’Haïti. Paris: E. Dentu, 1862.

Bulmer-Thomas, V. The Economic History of the Caribbean Since the Napoleonic Wars. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Cadet, Jean-Jacques. « L’aventure de la pensée socialiste en haiti. Une analyse des oeuvres d’Antenor Firmin, Démesvar Delorme et Louis-Joseph Janvier. » Le Grand Soir. https://www.legrandsoir.info/l-aventure-de-la-pensee-socialiste-en-haiti-une-analyse-des-oeuvres-d-antenor-firmin-demesvar-delorme-et-louis-joseph-janvier.html

Comte, Auguste. A General View of Positivism. London: Tráubner and co., 1865.

Delorme, D. (Demesvar). Études sur l’Amérique. La Démocratie et le préjugé de couleur aux États-Unis d’Amérique. Les Nationalités américaines et le système Monroë. Bruxelles: H. Thiry-Van Buggenhoudt, 1866.

La Misère Au Sein Des Richesses: Réflexions Diverses Sur Haïti. Port-au-Prince: Editions Fardin, 1976.

Les Théoriciens au pouvoir. Causeries historiques. Paris: H. Plon, 1870.

L’Indépendance d’Haïti et la France, par Charolais. Paris: E. Dentu, 1861.

Denis, Lorimer and Francois Duvalier. Translated by Louis G. Lamothe. Problema de clases en la historia de Haiti: sociología política. Port-au-Prince: Al Servicio de la Juventud, 1948.

Dubois, Laurent. Haiti: The Aftershocks of History. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2012.

Dupuy, Alex. Haiti in the World Economy: Class, Race, and Underdevelopment Since 1700. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1989.

“Class formation and underdevelopment in nineteenth-century Haiti,” Race & Class 24, no. 1 (1982): 17-31.

Edouard, Emmanuel. Essai Sur La Polítique Intérieure D’Haïti: Proposition D’une Politique Nouvelle. Paris: A. Challamel, 1890.

Fatton, Robert. The Roots of Haitian Despotism. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007.

Firmin, Joseph-Anténor. The Equality of the Human Races: (Positivist Anthropology). New York: Garland Pub., 2000.

Lettres De Saint Thomas Études Sociologiques, Historiques Et Littéraires. Paris: V. Girard E. Brière, 1910.

Hunt, Benjamin S. Remarks on Hayti as a Place of Settlement for Afric-Americans: and on the Mulatto as a Race for the Tropics. Philadelphia: T. B. Hugh, 1860.

Janvier, Louis-Joseph. Les Détracteurs de la race noire et de la république d’Haïti (avec Jules Auguste, Clément Denis, Arthur Bowler et Justin Dévost). Paris: Marpon et Flammarion, 1882.

La République d’Haïti et ses visiteurs (1840-1882); réponse à M. Victor Cochinat (de La Petite presse) et à quelques autres écrivains. Paris: Marpon et Flammarion, 1883.

L’Égalité des races. Paris: G. Rougier, 1884.

Haïti aux Haïtiens. Paris: A. Parent, A. Davy, 1884.

Les Antinationaux, actes et principes. Paris: G. Rougier, 1884; Port-au-Prince: Panorama, 1962.

Les Affaires d’Haïti (1883-1884). Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion, 1885; Port-au-Prince: Panorama, 1973.

Les Constitutions d’Haïti, 1801-1885. Paris: C. Marpon et E. Flammarion, 1886; Port-au-Prince: Fardin, 1977.

Le Vieux Piquet ; scène de la vie haïtienne. Paris: A. Parent, 1884.

Du Gouvernement civil en Haïti ; avec le portrait de l’auteur. Lille: Le Bigot frères, 1905.

Jean, Eddy Arnold, and Justin O. Fièvre. Les Idées Politiques Au XIXème Siècle. Port-au-Prince: Editions Haiti – Demain, 2011.

Joachim, Benoit. “La estructura social en Haití y el movimiento de independencia en el siglo XIX,” Secuencia no. 2 (1985): 171-182.

Laguerre, Michel. The Military and Society in Haiti. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993.

Laroche, Léon. Haïti: Une Page D’histoire. Paris: A. Rousseau, 1885.

Lewis, Gordon K. Main Currents in Caribbean Thought: The Historical Evolution of Caribbean Society in Its Ideological Aspects, 1492-1900. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

Leyburn, James Graham. The Haitian People. New Haven, London, 1966

Manigat, Leslie François. 2001. Eventail d’histoire vivante d’Haiti: des préludes à la Révolution de Saint Domingue jusqu’à nos jours : (1789-1999). Port-au-Prince, Haiti: CHUDAC.

Moses, Wilson Jeremiah. 1978. The Golden Age of Black nationalism, 1850-1925. Hamden, Conn: Archon Books.

Nicholls, David. From Dessalines to Duvalier: Race Colour, and National Independence in Haiti. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Haiti in Caribbean Context: Ethnicity, Economy, and Revolt. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Price, Hannibal. De La Réhabilitation De La Race Noire Par La République D’Haïti. Port-au-Prince: Impr. J. Verrollot, 1900.

Ramsey, Kate. The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Sibeud, Emmanuelle. « Comment peut-on être noir ? » Le parcours d’un intellectuel haïtien à la fin du XIXe siècle. » Cromohs, 10 (2005): 1-8

< URL: http://www.fupress.net/index.php/cromohs/article/view/15622/14489#.WEpL8qf0uvs>

Sheller, Mimi. Democracy After Slavery: Black Publics and Peasant Radicalism in Haiti and Jamaica. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000.

Thoby, Armand. La question agraire en Haïti. Port-au-Prince, 1888.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Haiti, State against Nation: The Origins and Legacy of Duvalierism. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1990.

Leave a Reply