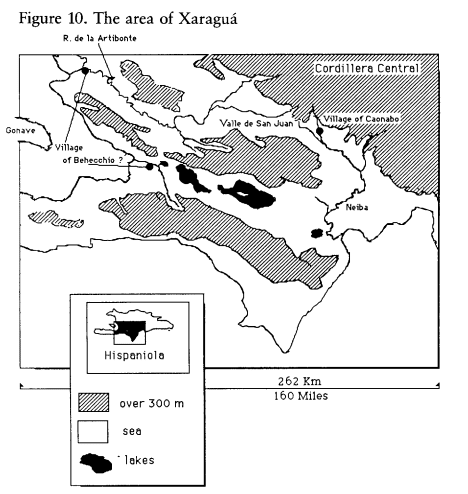

The history of Xaragua, perhaps meaning Country of the Lakes, remains elusive. Despite its recognition by authorities such as Las Casas as the zenith of the Taino chiefdoms on Hispaniola, and perhaps in the entire Caribbean, we know little about it besides what the Spanish chronicles have described. Indeed, with the exception of Behechio and Anacaona, we know nothing about its previous rulers. Furthermore, archaeological research in Haiti has been less rich than other parts of the Greater Antilles, so who knows what may be buried under Leogane and Port-au-Prince that could shed light on the indigenous past of the region? However, since Xaragua was recognized as having the most refined manners and language, the most beautiful women, served as the “court” of the island, perhaps uniquely practiced irrigation, produced the best cotton and batatas, and included the largest number of nobility or nitaino, one cannot help but think of what the sources on Xaragua reveal about the nature of Taino cacicazgos or polities. Despite the paucity of our sourcs, a perusal of Xaragua may reveal greater dynamics and accomplishments of Taino civilization.

First, Xaragua’s demographics and resources. According to Oviedo, the area around modern-day Lake Azuei included several villages. Indeed, as late as 1515, when he visited the area, it was still full of large villages. These villages, according to Oviedo, fed on the marine life that lived in the lake, since this was a major source of protein in the Taino diet. In addition, the Taino villages in proximity to sources of water, like Lake Azuei and other bodies of water, facilitated the use of ditches for the irrigation of their conucos. The proximity of seafood protein, bodies of water, and irrigation increased the density of population. This, in turn, meant the caciques of Xaragua were in a more powerful position since they could draw on the tribute of their subjects for resources, trade, and redistribution through areytos and other communal services. This large, densely populated cacicazgo could support a large class of nitaino, too, perhaps over 100 or 200, if Las Casas is to be trusted. In fact, according to Oviedo, the main village of the rebel cacique, Enrique, could have held 1500 residents in previous times before the decline of the indigenous population. If that figure is reliable for a Taino village near a lake, then Xaragua’s population may have included villages with perhaps several thousands of residents living around and near Lake Xaragua. This sustained the large population of “lords” (in the Spanish parlance of the time) which could be supported through the labor of the rest of the community, a sign of relative wealth and abundance with sufficient resources. If, as d’Anghiera claimed, the caciques assigned occupations to his subjects, such as fishing, hunting, and farming, the caciques of Xaragua must have benefited from a tremendous population to extract labor services or tribute from. The nitainos could have been subordinates who also measured property of estates or cacicazos, since land was likely held by the family unit or village. The surplus production of the chiefdom probably facilitated the rise of more specialized behiques and schooling for elites who learned the history of the chiefdom through songs and poems. This, in turn, must have led to more refinement in language and courtly manners, the organization of areytos, and, perhaps, the cacicazgo’s ability to attract dependents, alliances through marriage, or trade.

Moreover, d’Anghiera alluded to Anacaona’s village near the Xaragua capital which served as a storage center for her treasure or wealth, which consisted of finely made wooden stools or duhos plus everyday bowls, vases and pottery. The finely crafted duhos she gifted to Bartolome Colon were supposedly produced in La Gonave, by women specialists. Considering the amount of time and skill that went into producing the finest duhos, often of guayacan and featuring gold incrustations and intricate patterns and animal or human features, Xaragua was capable of producing one of the most highly valued objects in the Taino sociopolitical system, duhos. Indeed, Xaragua’s fine cotton, later an item of tribute to the Spanish after Behechio agreed to render tribute to the Adelantado, must have been cultivated in relatively large amounts and used to produce naguas, hamacas, items for everyday use, and for trade with other cacicazgos, on the island and perhaps in Cuba and beyond. If Careibana, for instance, was a port with a large population, perhaps Xaragua sent and received canoes bringing items of trade. This seems rather likely, since the Spanish remembered the Taino as fond of trade or exchange. Furthermore, Oviedo mentioned a lake which contained fine salt, probably exploited and exchanged by the Taino from its origin in the Bainoa province before 1492. One could see Xaragua’s salt, cotton, surplus casabe, and fine duhos as items of trade and gifts for guanin or other imported goods. This, in turn, enhanced the cacicazgo’s position since the finest cotton goods were used for chiefly adornment and naguas, just as the more elegant duhos, an item of particular ritual and spiritual importance attached to the caciques, could have been gifts or objects of exchange between Xaragua and other chiefdoms. Indeed, the rich resources of the cacicazgos that sustained a refined elite could also have served the cacicazgo in its relations as other caciques were taught areytos or the aristocratic manner of Xaragua in exchange for allegiance, tribute, or alliance. This is the only way Xaragua could have possibly reached over 200 nitainos. One, perhaps, sees a glimpse of this in the lavish pomp, ceremony, areytos and feasting for the Adelantado and Ovando when they visited Xaragua’s royal capital. If Xaragua was capable of organizing large festive dances, feasts, and entertainment that even included a mock battle (perhaps meant as a message to the Spanish of their military potential?) for the Guamiquina of the Christians, then they were clearly able to draw from vast resources. Indeed, if wives of caciques, such as at least one of Behechio’s, could be buried with their deceased husband, the Taino society was able to sacrifice the lives of women, a sign they could afford to lose the labor of women so vital in the production of casabe. Caciques were also buried by being wrapped in cotton bandages, another sign of the extensive resources of the Taino who used cotton for burial purposes, cemis, and clothing. The Taino likewise had sufficient leisure time for the construction of plazas for the batey, which in Xaragua, could have likely included more than one plaza. Alas, any evidence of batyes in Xaragua may be lost under Port-au-Prince or Leogane.

The nitainos and lesser caciques would have been included in meals, eating from the fine ware of the Xaragua caciques as well as, through marriage, receiving favor or potential connections as kin of the next heir. Indeed, Behechio was said to have had at least 30 wives. These women, presumably all kin of lesser caciques and allies of Behechio, gave him tremendous power and connections around the island. First, in marriage, lords often had to give stones, shells, and guanin to the fathers, according to Las Casas. Behechio undoubtedly had access to great wealth to be able to marry so many women. His wives’ relatives may have felt invested in the cacicazgo through kinship ties sealed by marriage, the sharing of Xaragua areytos, and redistribution of the cacique’s goods when he or she died (their property was split between relatives and affiliated visitors). Besides, through the marriage of his sister to Caonabo in Maguana, a powerful cacique who was perhaps from the Bahamas, Behechio ensured Xaragua’s influence extended into the eastern part of the island. For example, when the Adelantado first crossed paths with Behechio, it was on the Rio Neyba. According to some, such as Hermann Corvington, Behechio was actually en route to engage the Spaniards in combat. Others, like chronicler d’Anghiera think Behechio was on a military campaign against recalcitrant rebels or perhaps to pacify a province that was once loyal to Caonabo, already killed by the Spanish conquerors. Either way, Behechio’s alliance with Maguana had given it some influence to the east. Further, if succession was matrilineal, a child of Caonabo and Anacaona could have become a heir or successor to Behechio. This would have made Caonabo, not native to the island, more secure as the Xaragua chiefdom could potentially have been ruled by his progeny.

Hence, marriage alliances must have played a great role in cementing alliances and increasing the investment of lesser caciques and nitainos in the success of a matunheri cacique like Behechio. This was perhaps also done in the west, in Haniguayaba and possibly as far as Cuba. In the west, according to Las Casas, the cacique of Haniguayaba acted as independent lord because of his distance from Xaragua. However, there is an implied fealty or at least semblance of subordination to Behecio even as far west as the “boot” of Haiti. Perhaps some of Behechio’s 30 wives’ families included caciques and nitainos from these western provinces, who would also have been drawn into Xaragua’s cultural orbit through its elegant court, lavish areytos, and food surplus. Indeed, this seems to have been the case in the modern Sud-Est of Haiti, too, where Yaquimo and other regions were part of Xaragua’s sphere of influence. In fact, aligning with Xaragua may have given lesser caciques and nitainos the protection they needed from other communities. If, as claimed by Las Casas, Taino chiefdoms often went to war over land, seafood resources and over failed promises to deliver a bride, a powerful cacique like Xaragua could have supported dependents.

Clearly, Xaragua’s control of its resources, its ability to cultivate dependents, and the highly refined nature of its court must have made it a paramount chiefdom of the island. The alliance with Caonabo, albeit rather late in the precolonial period, likely led to it becoming the dominant cacicazgo on the island. Shifting alliances aside, Behechio’s court must have represented the zenith of the island’s indigenous civilization. And due to the close association between religion and power and religion and culture, one may speculate that some of the myths and traditions recorded by Fray Ramon Pané in the other part of the island reflect at least some of Xaragua’s myths and traditions. If the areytos and some of the cemis of Xaragua were influential across the island, then surely Pané’s brief account offers some insights into the nature of Xaragua, too. After all, d’Anghiera reported that the areytos were part of the preserved traditions at the houses of the caciques, where behiques trained their sons. Due to its wealth, cultural power, and the probably higher number of behiques who may have been partly freed from everyday labor, one suspects that Xaragua influenced other cacicazgos through its spiritual practices and behiques.

Unfortunately, the finest cacicazgo was defeated with little (overt) resistance. After Caonabo’s heroic decision to destroy the Europeans left at La Navidad, he was later trapped and defeated. Why wasn’t Behechio involved in Caonabo’s battles with the Europeans? As the most powerful cacique, one would think he was certainly aware of the Spanish and their misdeeds and exploitation of indigenous people in other cacicazgos. Did he really think they would never come to Xaragua? The Spanish sources suggest Anacaona was responsible for Xaragua’s rapprochement with the Spanish, although one must question their narratives. After all, Anacaona’s husband had been killed by the invaders and her homeland’s autonomy was next on the chopping block. We are inclined to believe that Anacaona was perhaps plotting something against the Spanish, although it seems unlikely that Roldan and his band of robbers would have been the allies to use against the official colonial government. Either way, Behechio and Anacaona agreed to pay tribute in cotton and casava bread. This happened even as Behechio and Anacaona could have likely murdered the entirety of the Spanish company of the Adelantado. Perhaps Anacaona, after seeing the destruction wrought by the Spanish in other parts of the island, hoped for a situation in which the cacicazgo of Xaragua would survive by paying tribute and, over time, revolting once familiarity with European weapons and technology was achieved. Is this why she was so intrigued by the caravel of the Spaniards? Or, perhaps, was fatalism spreading due to the prophecy given by a cemis that clothed strangers would conquer them? Either way, Xaragua’s lamentable end was achieved when Ovando massacred perhaps 80 elites and killed Anacaona, destroying the most powerful cacicazgo of Hispaniola. With this ignominious massacre and deception, Xaragua’s capital was replaced by Spanish towns in which, as recalled by Las Casas, at Vera Paz, 60 or 70 European males were said to be married to women from the elite.

Works Consulted

Anghiera, Pietro Martire d’. De Orbe Novo: The Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D’Anghera. New York ; London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912.

Casas, Bartolomé de las. Apologética historia sumaria . [3. ed.]. México, 1967. Cassá, Roberto. 1990. Los Tainos de La Española. 3a ed. Santo Domingo: Editora Buho.

Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo, José Amador de los Ríos, and Madrid R. Academia de la historia. Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierrafirme del mar océano. Madrid: Impr. de la Real academia de la historia, 1851.

Granberry, Julian, and Gary S. Vescelius. Languages of the Pre-Columbian Antilles. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

Keegan, William F., and Florida Museum of Natural History. Taíno Indian Myth and Practice: The Arrival of the Stranger King. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007.

Moscoso, Francisco. Tribu y clases en el Caribe antiguo. San Pedro de Macorís, República Dominicana: Universidad Central del Este, 1986.

Nau, Emile. Histoire Des Caciques D’Haïti. 2. éd. publiée avec l’autorisation des héritiers de l’auteur par Ducis Viard. Paris: G. Guérin, 1894.

Oliver, José R. Caciques and Cemí Idols: The Web Spun by Taíno Rulers Between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009.

Stevens Arroyo, Antonio M. Cave of the Jagua: The Mythological World of the Taínos. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1988.

Vega, Bernardo. Los Cacicazgos De La Hispaniola. 3. ed. Santo Domingo: Fundación Cultural Dominicana, 1990

Wilson, Samuel M. Hispaniola: Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Leave a Reply