African American dancer, anthropologist, and choreographer Katherine Dunham enjoyed a lengthy relationship with Haiti. Beginning with her travels as a student at the University of Chicago in the 1930s, Dunham retained her connections to the island for the rest of her life. Moreover, Haiti, the subject of her memoir, Island Possessed, illustrates how important the Black Republic was for her conception of dance, her comprehension of Black Atlantic performance and racial pride. Dunham’s central use of Haiti for the development of Black Atlantic dance is an example of “Negritude Dance.” Dunham drew from folklore, anthropology, and a racial pride in which Haiti occupied a central role. Dunham’s thought influenced Haiti, too, leading to the growth of folkloric performance there and other sites in the Black Atlantic. The folk-modern dialectic and shifts in anthropological theory about Haitian dance and popular religion, particularly through the influence of scholars like Robert Redfield and Melville Herskovits, sheds additional light on the ideological context of Dunham’s relationship with Haiti. Furthermore, Dunham’s experiences with future Haitian president Léon Dumarsais Estimé, Jean Price-Mars and other Haitian intellectuals and folkloric performers, as well as direct experience with Vodou initiation, allowed her to develop a relationship with Haitian dance that challenged the observant-participant role of ethnography, making her a pioneer in dance anthropology.

The ideological context of Dunham’s engagement with Haiti begins with the indigéniste movement. Although African American intellectuals long before Dunham looked to Haiti as a potential home, source of inspiration, and example of black sovereignty, Dunham’s travels in Haiti included socializing and ethnographic work alongside Haitian intellectuals such as Price-Mars. Her interest in Haiti developed in a period when more attention was centered on the island nation by African Americans, especially during the Harlem Renaissance. During this period, writers such as Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, and Zora Neale Hurston wrote about Haiti.[1] These African-American writers and activists were in communication with Price-Mars and the young generation of Haitian intellectuals who looked to Haitian folklore, such as Jacques Roumain. In order to resist the US Occupation more effectively, these Haitian intellectuals believed that they had to bridge the divide between elites and the peasant masses and reorient national identity away from Francophile expressions.[2] One of the significant calls of the indigéniste movement was an explicit demand from Price-Mars that Haitian musicians, composers, artists, poets, and novelists look to Haitian folklore as a source for their artistic works. Through journals such as La Revue Indigène, Haitian poets and intellectuals put this into practice by incorporating folk themes, Vodou religious references, and self-affirming messages about people of African descent in their work.[3] Haitian composers, such as Ludovic Lamothe, and Werner Jaegerhuber, studied Haitian folk music and Vodou ritual song, adapting it to Western classical styles and thereby refining it as Price-Mars had called for.[4] Haitian indigenists believed this was necessary to cultivate Haitian national identity, unite the country against the racist US Occupation, and develop a truly national aesthetic. This intellectual climate shaped Dunham’s relationship to Haiti because it was with these Haitian intellectuals she engaged in her early trips to the island.

Over time, indigénisme birthed the Griots, an organization rooted in noirisme, an intellectual movement that advocated essentialist readings of race. Noirists promoted dark-skinned Haitians as the only authentic or true representatives of Haiti.[5] Noirists and indigenists represented the two ideologies which dominated Haitian interest in folklore and Vodou, which was elevated to a proper religion in the works of Price-Mars. His ethnographic work included extensive trips among the Haitian peasantry to document their religious practices, folklore, and demonstrate the continuity of African influences in the formation of the Haitian people. Price-Mars showed that the Haitian peasants were, according to Imani Owens, “Neither primitive threat nor nostalgic anecdote to modernity, the folk themselves are modern. By highlighting the historicity of the folk, Price Mars is able to emphasize the material circumstances of their lives and argue for their role in strategies of resistance.”[6] To Price-Mars, “Tales, legends, riddles, songs, proverbs, beliefs thrive with an extraordinary exuberance, magnanimity, and ingenuity. These are the superb human materials from which are molded the warm heart, the multi-consciousness, the collective mind of the Haitian people!”[7] This revolutionary insight in Haitian social thought paved the way for inter-class solidarity and nationalist fervor in Haiti. Thus, by the end of the 1930s, Haitian nationalists unaffiliated with the indigénistes were also willing to promote folklore to celebrate Haitian national identity and promote Haiti on the international stage. Early folkloric troupes emerged at this time, and by the 1940s, folkloric performances were actively sponsored by leaders such as Élie Lescot. Lina Blanchet also contributed to the early Haitian folkloric movement by using folkloric musical scores, incorporating these traditions in her piano performances, and introducing her voice and piano students to these traditions.[8] Clearly, folkloric dance and singing became, among the Haitian middle-class and elite, a style appropriate for national representation. Katherine Dunham herself appears to have influenced this shifting reception after a performance at the Rex Theatre in 1937.[9] But these shifts in Haitian social reception of Haitian folkloric dance and the Vodou religion, partly a result of resurgent Haitian nationalist politics, also influenced Katherine Dunham.

In addition to the influences of Haitian intellectual thought during the time, Dunham’s first trip to Haiti was shaped by American anthropology of the epoch. Her research was supported by Northwestern University’s Melville Herskovits and Robert Redfield of the University of Chicago. After receiving funds for travel in the West Indies from the Rosenwald Foundation, Dunham left to study dance among different Caribbean societies in Haiti, Martinique, Jamaica, and Trinidad. Her approach to Caribbean societies at the time bore the imprint of Robert Redfield’s notion “folk-urban continuum” to understand cultural change.[10] Redfield’s idealized peasant community of “utopian primitives” also shaped Dunham’s early perspectives on Caribbean dance.[11] However, Dunham received additional assistance from Herskovits, who helped connect her to segments of the Haitian political and social elite. More importantly, Herskovits’s own study of Haitian rural life, Life in a Haitian Valley, was only recently published in 1937 and shaped Dunham’s understanding of African cultural retention in the Caribbean. For example, Herskovits noted how Vodou adherents in Mirebalais attended ritual ceremonies, but rushed to the Catholic mass the following morning. He also noted the European influence on the melodic line of Haitian music. This indicates a cultural fusion of African and European customs in Haiti which Herskovits championed for the study of African Diaspora anthropology.[12] Dunham acknowledges her debt to Herskovits in Island Possessed but scholar Hannah Durkin argues, “Herskovits and his contemporaries read cultural practices in historical terms, therefore helping to reinforce an illusory concept of cultural purity and disregarding the Black Atlantic as a key site of modernity.”[13] Dunham, however, championed Haitian folkloric dance and black racial pride as modern while acknowledging cultural creolization. Dunham also differed from fellow anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston on the subject of Haiti. Hurston’s Tell My Horse, for instance, did not criticize the US Occupation of Haiti. Furthermore, Hurston’s ethnography played on exoticism and primitivism to depict Haitian society as occupied by liars and seemingly justified US paternalism.[14] Dunham, on the other hand, championed Haiti as a center for negritude and black modernity, best exemplified through her relationship with President Estimé of Haiti.

Negritude, for Dunham, was rooted in Estimé’s politics, racial pride, and humanist principles. Psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, who helped her receive funding from the Rosenwald Foundation, paved the way for her “receptivity to the thinking of Estimé.”[15] Dunham’s experience with humanism from figures like Fromm and her perceptive reading of Haitian society and politics through Estimé meant that negritude entailed modernity and racial pride. To Dunham, Estimé “was the first in defining the concept of negritude, the placing of the black race in its proper perspective and accord with the rest of the world, a prise de conscience.”[16] She also associated the ideas of Price-Mars and Estimé with Haitian economic development and social progress, admiring the latter for reforming the Haitian educational system and improving government services.[17] Consequently, negritude for Dunham did not entail primitivist readings of Haitian culture but a developed sense of racial pride and assertion of black humanity. And Estimé, who rose to power after a democratic revolution influenced by Haitian cultural nationalists, socialists, and black nationalists, exemplified her grand vision. This definition of negritude importantly evaded the racial essentialism of the noiriste camps in Haitian intellectual thought while supporting modern reforms. The role of folklore for this conception of negritude was intended for reasserting the dignity and equality of African and Black Atlantic arts and dance, thereby developing a modern national consciousness and aesthetic. Dunham’s conception of negritude clearly championed such a perspective, since she refers to her relationship and exchange of ideas with Estimé as being “one with the avant garde of negritude.”[18]

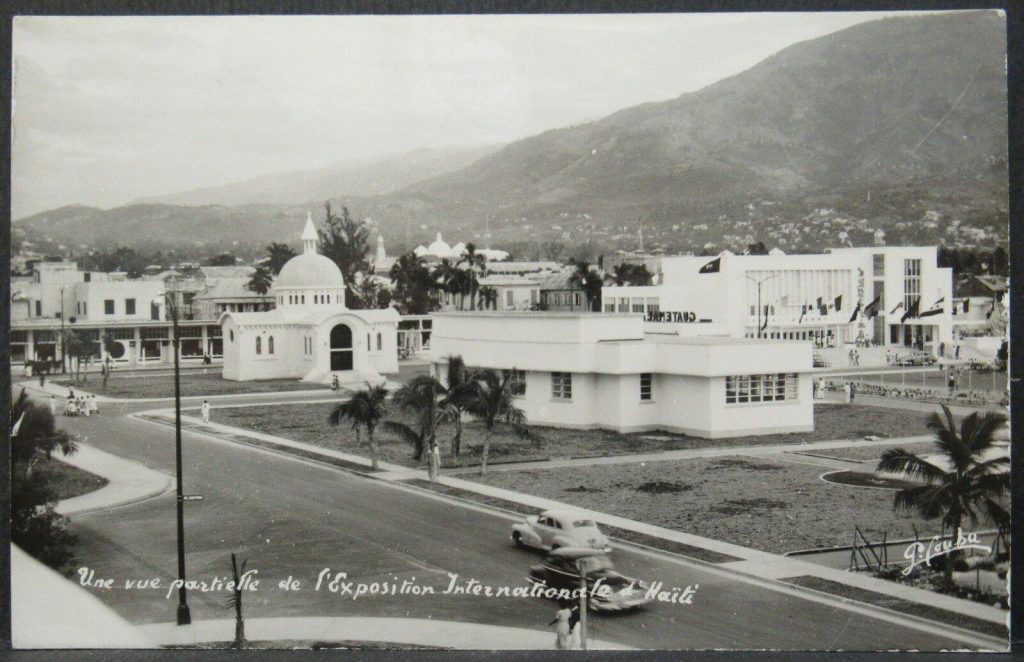

It was also during the presidency of Estimé when folkloric dance skyrocketed to importance for Haitian representation on the national stage. Aforementioned folkloric troupes and classical composers were active in the 1930s, but under Estimé the opening up of Port-au-Prince society to folkloric performance and the use of folkloric dance to represent Haiti expanded exponentially. For example, in the 1940s, Port-au-Prince nightclubs began to feature dance music based on folkloric styles and Vodou ritual music, especially the Vodou-jazz orchestras of the 1940s. These bands, such as Jazz des Jeunes, fused folkloric and Vodou rhythms and references with jazz and Cuban-inspired styles to entertain and assert Haitian identity.[19] Folkloric groups from the pre- Estimé years who represented Haiti in international performances were also expanding, including choirs, dance troupes, and painters associated with the famous Centre d’Art in Port-au-Prince. The growing tourist sector fueled the expansion of folkloric performance because, as suggested by Brenda Plummer, the development of Haiti as a major research field in the social sciences and the search for authenticity made it more attractive to American tourists. Haitian “primitive” and quaint customs were no longer read as menacing and the blackness of Haitians added to the exotic and colorful nature of the locale.[20]Folkloric dance and Vodou ritual provided excellent opportunities for tourists to use as a vehicle for authenticating a primitive Haiti of their imagination. Although Estimé was personally opposed to the Vodou religion for allegedly distracting the Haitian lower classes from addressing their “real” problems, he, as part of the broader ideological shift in Haitian society, saw the value of folkloric dance for expressing Haitian identity and boosting state revenue.[21] In fact, Estimé further promoted folkloric performance as a symbol of Haitian identity and progress for the Bicentennial Exposition of Port-au-Prince. A showcase for Haiti on the international stage, Estimé razed slum areas, erected new monuments, and featured folkloric dance, music, and arts for the Exposition.[22] While his intent was clearly to promote Haitian tourism, the fact that he accompanied folkloric performance with novel urban improvement and monuments indicates that Haitian politicians did not harbor any primitivist delusions. Folkloric dance and music represented the Haitian nation, brought members of different social classes together, and served Haitian interests in Pan-American conferences, performances, or competitions. Indeed, folklore, according to Ramsey, “held a privileged status under Estimé, a long-term supporter of the ethnology movement.”[23] The Haitian folkloric movement similarly promoted local talent and created opportunities for Haitian musicians, dancers, and painters to travel abroad, hone their technique, and, in some cases, like Jean-Léon Destiné, perform internationally with Katherine Dunham’s company.[24]Moreover, folkloric performance could be used by proponents of noirisme and cultural authenticity to critique light-skinned elites and others for not promoting Haitian identity, negritude or social equality. Of course, this discourse was cynically exploited by François Duvalier and other noiristes to camouflage their own class interests as the rising middle class, but it nonetheless reveals the counter-hegemonic capacity of Haitian music.[25]

However, without Dunham’s research and elevation of Haitian folk dance abroad, the explosion of Haitian folk music in the 1940s and 1950s would have likely been stalled. For example, Dunham surprised Port-au-Prince high society during a dance performance at Rex Theatre that incorporated aspects of Vodou ritual dance. According to Kate Ramsey, this April 1936 performance, which included Price-Mars and René Piquion in attendance, featured Vodou dance during a segment of Danse Rituel de Feu by Manuel de Falla. Dunham later performed Haitian folkloric dance for the concert stage in 1938, under official wishes of Haitian government, for the Haitian Coffee Fest at Howard University.[26] Dunham later wrote that her Rex Theatre performance helped open doors for her in Port-au-Prince’s upper-class mulatto families, as well as a becoming a partially successful bridge for the color divide in Haitian society. Her audience included the social elite of Port-au-Prince as well as members of the rising middle class and intelligentsia.[27] Thus, folkloric dance was already connecting Haitians of different class-color backgrounds. Considering that Vodou was still penalized by the legal codes in Haiti at the time, excepting “social dances,” Dunham’s bold move demonstrates how negritude for her was rooted in a humanist sensibility that valorized African-derived traditions and aesthetics.[28] Dunham’s future US performances, which combined various Caribbean folk styles after returning from the Caribbean, similarly stimulated interest and audiences for Afro-Caribbean dance, although adding her formal training and technique.[29] Thus, Dunham’s essential role in promulgation of Haitian folklore for international audiences simultaneously assisted Haiti on the international stage while facilitating the development of a cultural shift in the Haitian arts world. Both Dunham and Estimé participated in this process.

[1] Mary Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915– 1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 291.

[2] Michael Largey, Vodou Nation: Haitian Art Music and Cultural Nationalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 51.

[3] David Nicholls, From Dessalines to Duvalier: Race Colour, and National Independence in Haiti (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 159.

[4] Michael Largey, Vodou Nation: Haitian Art Music and Cultural Nationalism, 52.

[5] Gage Averill, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey: Popular Music and Power in Haiti (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 55.

[6] Imani D. Owens, “Beyond Authenticity: The US Occupation of Haiti and the Politics of Folk Culture,” Journal of Haitian Studies 21, no. 2 (2015): 350, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43741134.

[7] Jean Price-Mars, So Spoke the Uncle, trans. Magdaline W. Shannon. (Washington: Three Continents Press, 1983), 173.

[8] Gage Averill, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey: Popular Music and Power in Haiti, 57.

[9] Kate Ramsey, “Katherine Dunham and the Folklore Performance Movement in Post-US Occupation Haiti,” in Katherine Dunham: Recovering an Anthropological Legacy, Choreographing Ethnographic Futures, ed. Elizabeth Chin (Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2014), 58.

[10] Joanna Dee Das, Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 31.

[11] Joyce Aschenbrenner, Katherine Dunham: Dancing a Life (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 47.

[12] Melville Herskovits, Life in a Haitian Valley (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1937), 181, 263.

[13] Hannah Durkin, “Dance anthropology and the impact of 1930s Haiti on Katherine Dunham’s scientific and artistic consciousness,” International Journal of Francophone Studies 14, no. 1-2 (2011): 11.

[14] Mary Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915– 1940, 288.

[15] Katherine Dunham, Island Possessed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 42.

[16] Ibid, 46.

[17] Ibid, 42.

[18] Ibid, 144.

[19] Gage Averill, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey: Popular Music and Power in Haiti, 59.

[20] Brenda G. Plummer, The Golden Age of Haitian Tourism (New York: Columbia University-New York University Consortium, 1989), 15.

[21] Katherine Dunham, Island Possessed, 26.

[22] Matthew J. Smith, Red & Black in Haiti: Radicalism, Conflict, and Political Change, 1934-1957 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 107.

[23] Kate Ramsey, “Vodou and nationalism: The staging of folklore in mid‐twentieth century Haiti,” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 7, no. 2 (1995): 357.

[24] Millery Polyné, From Douglass to Duvalier: U.S. African Americans, Haiti, and Pan Americanism, 1870-1964 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010), 157.

[25] Matthew J. Smith, Red & Black in Haiti: Radicalism, Conflict, and Political Change, 1934-1957, 60.

[26] Kate Ramsey, “Katherine Dunham and the Folklore Performance Movement in Post-US Occupation Haiti,” 62.

[27] Katherine Dunham, Island Possessed, 155.

[28] Kate Ramsey, “Katherine Dunham and the Folklore Performance Movement in Post-US Occupation Haiti,” 52.

[29] Hannah Durkin, “Dance anthropology and the impact of 1930s Haiti on Katherine Dunham’s scientific and artistic consciousness,” 23.

Bibliography

Aschenbrenner, Joyce. Katherine Dunham: Dancing a Life. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Averill, Gage. A Day for the Hunter, a Day for the Prey: Popular Music and Power in Haiti. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Batiste, Stephanie L. “Dunham Possessed: Ethnographic Bodies, Movement, and Transnational Constructions of Blackness.” Journal of Haitian Studies 13, no. 2 (2007): 8-22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41715354.

Chin, Elizabeth (ed). Katherine Dunham: Recovering an Anthropological Legacy, Choreographing Ethnographic Futures. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2014.

Dash, J. Michael. Haiti and the United States: National Stereotypes and the Literary Imagination. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Dee Das, Joanna. Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Dunham, Katherine. Dances of Haiti. Center for Afro-American Studies, University of California, Los Angeles, 1983.

___. Island Possessed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

___. “Open Letter to Black Theaters.” The Black Scholar 10, no. 10 (1979): 3-6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41163878.

“Dunham Technique:”Congo Paillette”.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003870/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

“Dunham Technique: “Yonvalou”.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003869/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

Durkin, Hannah. “Dance anthropology and the impact of 1930s Haiti on Katherine Dunham’s scientific and artistic consciousness.” International Journal of Francophone Studies 14, no. 1-2 (2011): 123-142.

Francis, Allison E. “Serving the Spirit of the Dance: A Study of Jean-Léon Destiné, Lina Mathon Blanchet, and Haitian Folkloric Traditions.” Journal of Haitian Studies 15, no. 1/2 (2009): 304-15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41715167.

Glissant, Édouard, Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

“Haiti Fieldwork.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003822/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

Herskovits, Melville J. Life in a Haitian Valley. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1937.

“Katherine Dunham on dance anthropology.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003840/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

“Katherine Dunham on Dunham Technique.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003814/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

“Katherine Dunham on her influence on American dance.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003839/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

“Katherine Dunham on the “pole through the body” in Dunham Technique.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003848/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

Largey, Michael D. Vodou Nation: Haitian Art Music and Cultural Nationalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Manning, Susan. “Modern dance, Negro dance and Katherine Dunham.” Textual Practice 15, no. 3 (2001): 487-505. doi:10.1080/09502360110070411.

Manuel, Peter (editor). Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009.

Métraux, Alfred. Voodoo in Haiti. New York: Schocken Books, 1972.

Nicholls, David. From Dessalines to Duvalier: Race Colour, and National Independence in Haiti. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Owens, Imani D. “Beyond Authenticity: The US Occupation of Haiti and the Politics of Folk Culture.” Journal of Haitian Studies 21, no. 2 (2015): 350-70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43741134.

Polyné, Millery. From Douglass to Duvalier: U.S. African Americans, Haiti, and Pan Americanism, 1870-1964. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010.

Plummer, Brenda Gayle. The Golden Age of Haitian Tourism. New York: Columbia University-New York University Consortium, 1989.

___. Haiti and the United States: The Psychological Moment. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992.

Price-Mars, Jean. So Spoke the Uncle. Translated by Magdaline W. Shannon. Washington: Three Continents Press, 1983.

Ramsey, Kate. The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

___. “Vodou and nationalism: The staging of folklore in mid‐twentieth century Haiti.” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 7, no. 2 (1995): 187-218. doi:10.1080/07407709508571216.

Renda, Mary A. Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915– 1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

“Shango.” Library of Congress video. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200003834/. (Accessed March 01, 2018.)

Smith, Matthew J. Red & Black in Haiti: Radicalism, Conflict, and Political Change, 1934-1957. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Haiti, State against Nation: The Origins and Legacy of Duvalierism. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1990.

Wilcken, Lois E. “Staging Folklore in Haiti: Historical Perspectives.” Journal of Haitian Studies 1, no. 1 (1995): 101-10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41715035

Leave a Reply