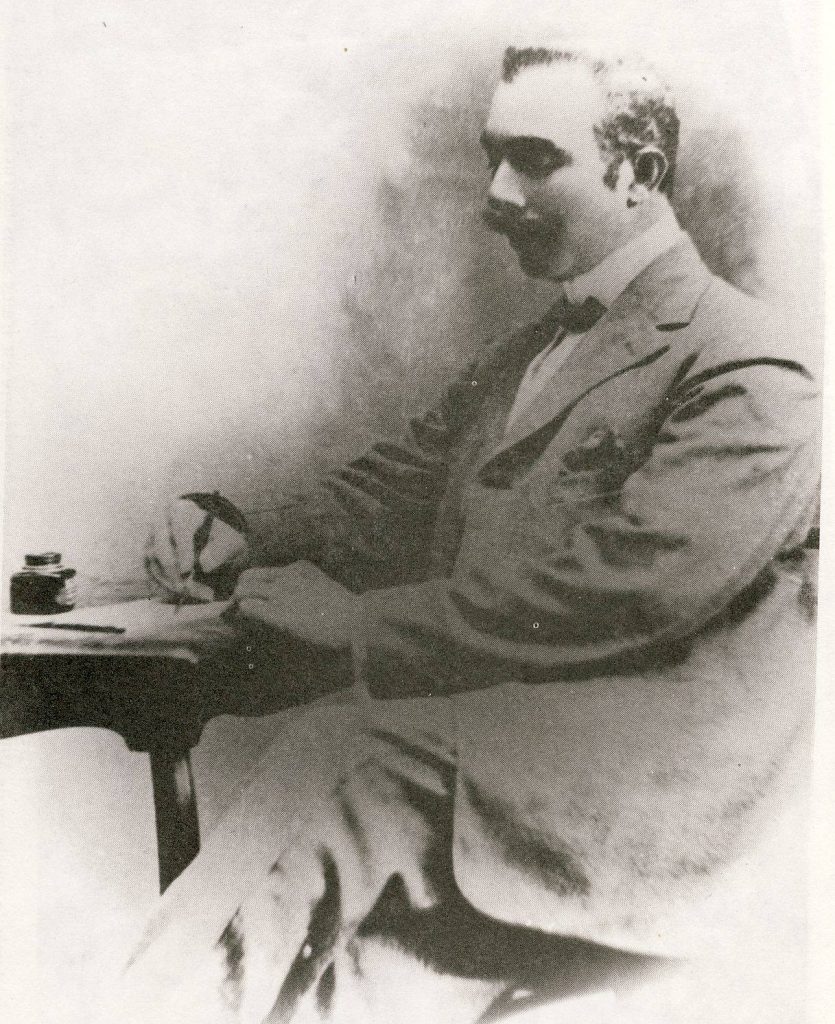

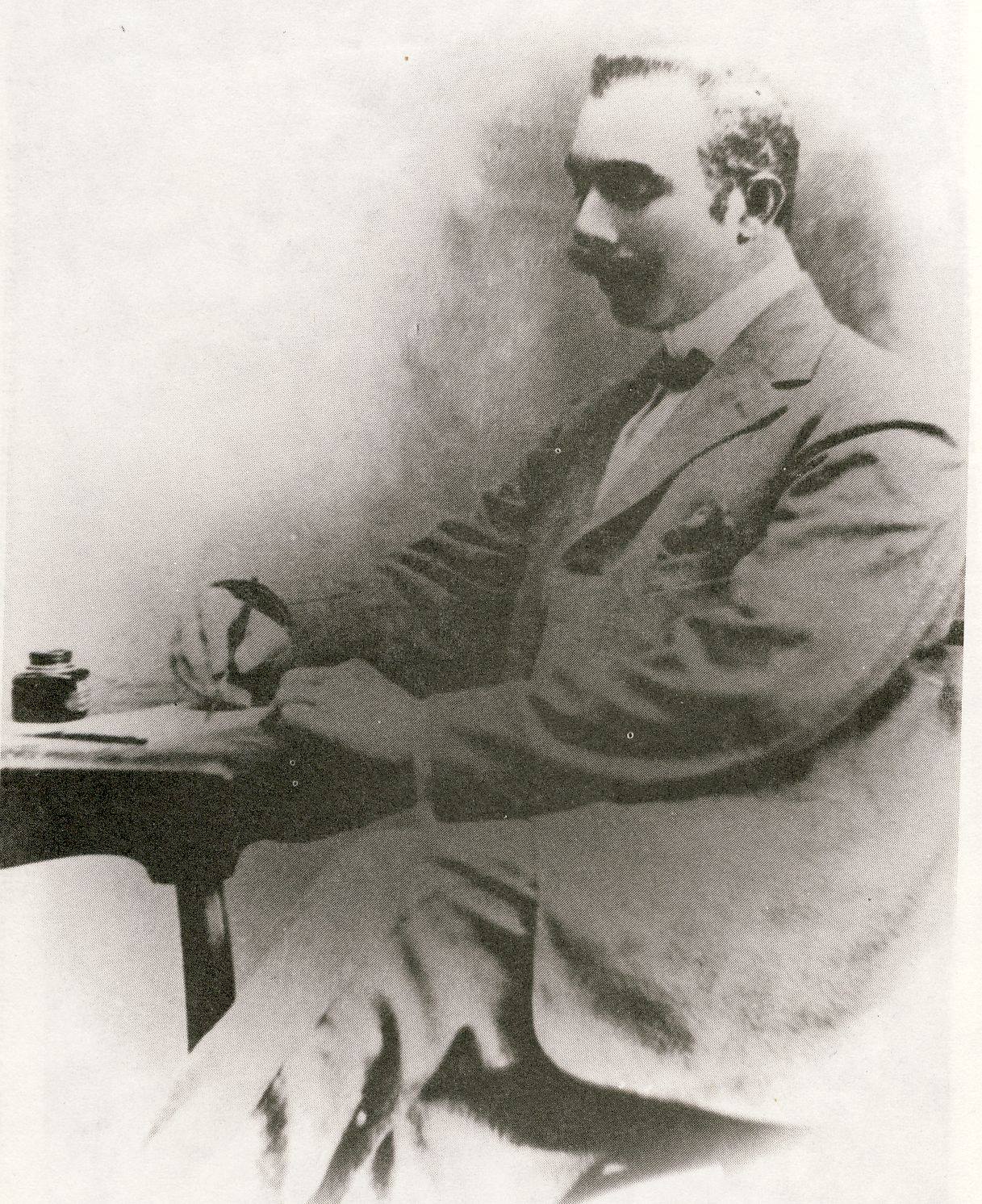

Well before the US Occupation of Haïti, Rosalvo Bobo was hailed as leader and proud nationalist among elite and international circles, while garnering the ire and even threats to his life from American operatives in Haïti. He was a deft politician with a clear insight into the geopolitical reality of early 20th century Haïti, including an understanding that ‘ti pays,’ or small-nation states, needed to find universal guarantees for their sovereignty in the face of bloody US political and economic expansion as well as continued, neo-colonial competition between the Great Powers in Europe and Japan as well at the time.

In 1914, Bobo served three months under the Davilmar regime as Minister of the Interior. Whilst he was bravely fighting in the North region, his fellow Firministe, Théodor Davilmar, betrayed him, sieged Port-au-Prince to the surprise of fellow cacos just a few towns over who were retaking cities from the zandolites[1]. Nevertheless, the dapper, charismatic grandson of a Northern prince under Salomon, fire-haired Bobo took the Port-au-Prince political scene by storm and was asked to work as a minister. From his first speech declaring his intent to hold office, tensions clearly arose between himself and the USA. Whereas the Haitian political elite like Charles Moravia discussed Bobo’s “idealism and constitutional principles” (Bobo was at his core a Firministe), and the British consul wrote back to London about Bobo’s refinement and sincere commitment to Haïti’s advancement from “poor administration,” the American consul to the Northern capital of Cap-Haïtien, Livingston (who, like Bobo was also a doctor) raised alarm at Bobo’s threat to American interests. “Le docteur Bobo…s’est efforcé de gagner de la popularité en se posant comme un ardent patriote don’t la mission serait de sauver Haïti de l’agression Americaine.”[2] A deft patriot could frightened Livingston and his ilk who had their eyes set on the Panama Canal and the important shipping highway between the islands of Cuba and Haïti known as the Windward Passage. After highlighting Bobo’s elite education in France, Livingston goes on to call Bobo a medical charlatan and political fraud in attempts to defame a seemingly honest man. From the start, American agents in Haïti interpreted Bobo’s nationalist rhetoric as dangerous and contrary to their direct material gain. Livingston saw Bobo’s keen ability to seamlessly enflame public sentiment as a form of nationalist populism that directly challenged the increasing economic ties between between US business interests and their numerous clients within Haitian society. The late Auguste de Catologne (of the famous Franco-Haïtiano-Martiniquais business family) tells historian Roger Gaillard in an interview in 1973 that Bobo was intensely anti-American, and as a reflex distrusted US politicians. Perhaps his distrust was merited as Bobo criticized the financial receivership and structural channels of US takeover seen in other nations like Hawaï and neighboring Dominican Republic. He reserved this contempt because the US was the most heavy-handed in its attempts to influence Haitian politics. Unlike France or even Germany, Washington alone demanded in exchange for official recognition of new caudillo governments that emerged such as Davilmar’s, that concessions around customs be made such that the Taft / Wilson regimes would control major sectors like banking.

As minister of the interior this nationalist flare famously led to a clash with his former protégé and student Joseph Justin, Haïti’s minister of foreign affairs under Davilmar. He, like Bobo, understood that considering the financial receiverships installed in several Central American nations, Haïti could not escape what seemed like a fated, Yankee financial takeover. However, he believed if Haïti would take an oppositional stance and negotiate an agreement with the United States, its supposedly inescapable domination would be less insulting, less humiliating.[3] When Joseph attempted to pass a revised version of a formal receivership plan in exchange for recognition the US government’s recognition of the Davilmar government, Bobo brandished and lashed his riding whip onto the table to the crowded legislative hall’s excitement. He roused the Port-au-Prince gaggle of curious citizens so well, that they yelled “Vive la liberté” to Joseph, perceiving the compromise as a formal capitulation of executive power to their northern neighbor. So roused was the crowd, that had it not been for Bobo’s elegant response on how the current government would drape itself in the flag and fight the slightest menace to Haïti’s sovereignty, Minister Joseph would not have been able to return to his post. Passions easily flared in the early 20th century around nationalism; Haïti was no exception. This ability to direct public opinion further heightened the fear in certain diplomatic circles that Bobo and his vision of Haitian nationalism served as an obstacle to financial control of Haïti, and on a greater scale, the fiscal domination of the Central America and thus the Panama Canal.

After his grand displays at the legislature, Bobo would soon after singularly sign a text calling for all Haitians to remember the heroics of their revolutionary forefathers in order to protect the nation’s sovereignty.[4] He takes time to mention how in history, the peiti peuples or members of small societies, have often been attacked by more powerful peoples for no other reason than the power differential that exists between them. Bobo implores his compatriots to not allow such a cowardly and criminal attack on smaller peoples to occur in the civilized 20th century. His texts would later inspire resistance movements like the cacos insurgency against the occupation. It followed a traditional, but ever-inspiring narrative centered on the heroic actions by 19th century Haitians. Although leaders frequently traced a historical line between the present and the nation’s independence leaders, Bobo raised new questions, for the 20thcentury before the Russian Revolution at least, about imperialism and the underdeveloped global majority. “If every Haitian were willing to fight in a similar way for its political and economic sovereignty, then they can make shockwaves again through their revolutionary spirit.” The Haitian Revolution, was thus a process whose goal was not yet achieved. In the early 1910s, US agent Livingston read this as a direct attack to the Monroe Doctrine at a pivotal moment in a changing global financial order. Finance-capitalism massaged through receivership and central bank seizures, a move to FIAT currency, and increasing discomfort with Germany’s role in the Americas as an alternative to investment in what Washington saw as its “backyard” coalesced into an ugly contempt for Rosalvo Bobo and for Haitian economic nationalism more generally. Unsurprisingly, the City Bank of New York successfully heisted Haitian stores of gold as the Théodore (Bobo’s political alliance) presidency waned in power. Haïti would thus have to depend on cash, eventually the dollar—the new Pan-American currency.[5]

Sensing a national fervor, Bobo began the ‘revolution’ path of stirring key chokepoints to his banner as a means of gaining the presidency, almost by acclamation, though the armed groupings of rural lumpen and a cross-class collaboration of farmers certainly played a role.[6] Davilamar’s presidency and base dripped away as public employees, even those in the North, remained unpaid. Upon learning that his allies from the North chose to rally with the Sam family, who had been organizing in the area for several months and acquired important allies, including the United States,[7] Dr. Bobo traveled eastward to the Dominican Republic. There he expanded his critique of finance imperialism born from receivership while working with Desiderio Arias. The eastern side of the island had already begun a receivership by the end of 1914. Together, the two operated in a transnational network espousing economic sovereignty and nationalism as the primary means to fight the emerging empire within the Caribbean. Their alliance and support for financial cooperation with Europeans in multilateral endeavors hardened Washington’s fear and frustration with Dr. Bobo, whom they assumed would foment anti-US feelings across the island; Haïti would then never accept a receivership structure and the Dominican Republic would uproot theirs, possibly leading both into German partnerships.

Note that as World War I began, the US grew even more suspicious of the German presence in the Panama Canal area. Furthermore, Germany and other European powers were willing to lend money to Caribbean governments with fewer concessions. When Bobo traveled westward to continue his now island-wide revolution in the North, despite attempts from US ministers in both nations to halt him, he again released a cutting critique of US financial domination in the Caribbean that albeit prescient, presaged his future exile by marines 4 months later in the ensuing occupation. In it he swears that he would never (repeated twice) deliver Haïti’s customs and finances to US control. He would prefer Haïti cease to exist than to do so. He goes on to detail how the financial agreement between the United States and the Dominican Republic was little more than “a makeup of fat emoluments for the financial advisors, where the slightest consequence means endless starvation and humiliation of the Dominican government. Never was an administrative supervision as oppressive, as galling to a small nation by a larger one.”

In his argument on his testimonies abroad in the United States and the Dominican Republic, he paints a jarring picture of how the industriousness that he so deeply respected from his esteemed friends in the United States was not recreated (as hoped) by financial receivership; instead, any pivot to financial dependence on the dollar by small countries led to hunger and difficult conditions for the poorest. Particularly, it would not materialize into large-scale industrial investment with local ownership of intellectual property. Nevertheless, the myth of American capital ingenuity created an ambivalence within certain sectors of the Haitian elite vis-à-vis US financial expansion, seen by Occupation rationalizers and apologists like Constantin Mayard. Bobo’s solution was a nationalist revolution that delegated rival foreign entities an equal stake as minority partners as Haïti would retake control of its finances. Haïti had suffered a long embargo and needed investment from beyond the French banks through which it serviced its debt for independence.

The tradition of multilateral agreements to negotiate full sovereignty reflected a geopolitical reality for a rapidly dollarizing Central America and Caribbean though approaches like Bobo’s which relied significantly on investments for exports (to fund necessary infrastructure projects) were still based on dependence on foreign capital.

The slow schism within the elite that would be elaborated and formalized during the occupation begins here, with many weighing their opinions of Boboistes and his patronage to the Polynice, Delva, and Zamor clans against their distaste with a foreign occupation (led by US Admirals Caperton and Beach, who through dinners, frequently courted Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien’s elite to measure public opinion and mine for information) that promised order, jobs, and early 20th century ideas of Anglo-industriousness.[8] For his part, Bobo continued a message that agreed things must change, but that Haïti needed a nationalist moment with a strong state, run by Haitians. Although French and British forces were cautious about the arrival of American troops, they had intimately worked together with the US legation during the aftermath of the murderous Sam debacle; only the German legation protested to the formal announcement of an occupation in August. For elites closely allied with German monopolies in business, the occupation threatened their wealth.

Rosalvo Bobo’s anti-imperialist rhetoric struck a strong note of resistance at a time when many in Haïti’s elite were comfortable playing German, French, British, and US interests off each other to get the best deal with the least teeth on Haïti. In the view of Secretary of State Bryan, he was at best a nationalist agitator, at worst a German ally during the war (World War 1). The United States forces took direct action to halt Bobo’s normal process of revolution by taking advantage of crisis in Cap-Haïtien and Port-au-Prince to intervene by sending marine forces to eventually occupy the nation. When viewed in totem, Bobo’s many tours, speeches, and letters played a decisive factor in creating an armed, organized resistance before the foreign occupation. In a report to Secretary of State Bryan and President Woodrow Wilson, the US State Department’s Division of Latin American Affairs cites two relevant, though poorly sourced, concerns among others: that Germans held control of 70 percent of business in Haïti with “no American commercial houses there” and that false politicians [presumably Bobo amongst others] were lying to a gullible public on how an American control of customs “would mean slavery for them [the public].”[9] In conjunction with numerous prior reports that Germans were stirring anti-US propaganda amongst Haïti’s well educated to secure a coaling base at Môle Saint-Nicholas, the report clearly underlines its authors; intent for a military invasion in Haïti where Germans and Haitian nationalists alike were obstacles to hegemony and monopoly in the Panama Canal region stretching the Pacific to the Atlantic.[10] Bobo’s alliances with the Northern and Artibonite cacos, which held major port towns where Germans definitely lived (because they produced coffee) and maintained patronage networks, shows how otherwise normal (in Western Europe, Russia, and the Americas) early 20th century nationalism based on a diverse economy became viewed as a threat to US interests. In an attempt to stop Bobo’s revolution and stymy his rhetoric, Admiral Caperton anchored ships in Cap-Haïtien in July 1915 to “protect lives and property” while also aiding Sam’s zandolites hold the city. Whereas he publicly threatened to land troops only to protect the lives of foreigners and property, his trusted Admiral Beach admitted their true intent, “C’était la faillite totale de sa [Bobo] revolution” (It was the complete collapse of Bobo’s revolution). Although Dr. Bobo, successfully evaded capture as head of the guerilla cacos, the US effectively perverted the usual order of cacos revolutions by preventing Cap-Haïtien’s capture, preventing troops from rallying before they make the slow train down to Port-au-Prince, allowing the then obviously defeated president to accept defeat and exile with loved ones. So when cacos soldiers successfully routed the government forces of President Villebrun Guillaume Sam, with the help of political refugees organizing at the Portuguese consul’s home and Boboiste leaders, the US operatives like Caperton quickly sailed for the capital to arrive before Bobo could triumphantly enter from the North and be acclaimed. They used the national shock stemming from President Villebrun Sam’s general’s massacre of political prisoners and the resulting public reprisals like hangings, to land troops from Guantanamo while the Haitian populace was still dazed by the fratricidal crisis. Proving that the violation of Haitan sovereignty by landing forces served as a direct means to counter Bobo, Admiral Caperton immediately tried to undercut the Revolutionary Committee preparing the city in addition to organizing the country for Rosalvo Bobo’s arrival from Terrier Rouge. Whereas most literature including Lyonel Paquin’s recounting begin the American Occupation with US troops landing in Port-au-Prince, a more nuanced view acknowledges that Admirals Caperton and Beach, and colonel Cole took a month to disarm cacos troops and convince scandalized Bobiste leaders that the US presence was temporarily maintaining ‘order’ until a new president established himself. Again, Bobo’s popular anti-imperial message that refused any fatalist submission to foreign forces prevented an immediate grab at the political and financial reigns despite the stupor of Port-au-Prince society in July and August 1915. The Revolutionary Committee’s early attempts to bypass naval representatives like Admirals Beach or Caperton and speak directly to president Wilson through Secretary of State Lansing demonstrates a political awareness to officially secure promises from Washington, while continuing to defy the authority of foreign military control. Although, neither attempts successfully achieved Bobo’s presidency or the dissolution of US naval forces, they inspired courage and fanned a nationalist spirit that would endure into the occupation, shaming collaborators while also waking Haitians out of the trauma caused by the aftermath of Sam’s death. National unity, they assured, were necessary to combat the instillation of a puppet state. Bobo acted as a formidable and premier organizer against US empire, even after troops landed, reaffirming Yveline Alexis’ dissertation on Charlemagne Péralte as his successor in organizing the cacos: “that Haitian resistance to the occupation was persistent and widespread.” Jean Dominique characterizes Bobo’s “genius” even better by noting that the doctor “had never mastered any particular texts on the imperial character of the United States, but was able to discern it, almost intuitively.”

If the US occupation of Haïti was thus partly inspired as a means to prevent the rightful chief executive from wielding power and mobilizing a nationalist wave in the Caribbean against financial neo-colonialism, then at its nascence, the project was doomed to fail precisely because Doctor Bobo inspired the resistance that survived to frustrate and challenge the American endeavor. As devoted Bobiste, Charles Zamor presciently noted, “with Bobo there would be immediate peace; without Bobo there would be a bloody pacification.”

[1] This battle must be seen as fratricidal to some extent as the Zamor family were military leaders with land and power in the North, North East, and Artibonite regions

[2] Rosalvo Bobo quoting the National archives

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid “Il serait très utile qu’on retînt la devise des Titans de ces épopées”

[5] The majority of global gold reserves reside in the Global North according to

[6] A note on ‘revolutions’: though the political turmoil inherent to overthrowing a president left considerable damage to infrastructure (walls riddled with bullets, fires, soldiers eating small and medium-sized farmers dry), there was never an attempt to kill opposing forces en masse. Rather, revolutionaries contented themselves with exiling their biggest political threats and oaths of subordination from pliable patrons of the opposing party. As Gaillard records second-hand from F. Yves of the Frères de l’Instruction Chrétien recalling their youthful days in the early 20th century, once while Port-au-Prince heralded a new chief executive into office, a man was beaten in the street in full view. Yves claims to have heard a woman crying out, “Oh, oh! A pa lan révolisyon, kouliyéa, yap touyé moun !” (Gaillard’s accents on the Creole ‘e’). Meaning, “Oh Oh! What, so now when doing revolutions they’re killing people !” If the sources are to be believed, this exclamation of shock, if not sarcasm, expresses an understanding that the revolutions of early 20th century Haïti were distinctly goal-oriented toward state capture (presidency and national bank) unlike a bloody civil war between partisans. These soldiers—only 1 to 3 generations away from the Revolutionary Army—rhetorically wielded nationalism and calls for political over a tabula rasa campaign. A sense of fraternalism remained.

Also note that in exile, Bobo would criticize Nord Alexis for having begun the process of strong-arming one’s way to the presidency (and ultimately preventing Bobo’s esteemed ideological mentor, Antenor Firmin, from the position).

[7] One of such allies included the Zamor family who had deep connections in the North, Artibonite, and North East. They and their affiliates, including the Péralte family, would later support Bobo only a few months later as Sam’s presidency entrenched the national crisis and committed violent atrocities. Importantly, Sam received strong support from the United States through Admiral Caperton, a staunch Bobo’s opponent. He even accompanied Sam on his march to the presidency.

[8] Many Sam partisans continued to harbor ill-will towards the cacos and Bobo supporters. Furthermore, as in French Canada, WWI resulted in a sharp decrease in French entertainment and access to the metropole. The Francophile elite reacted by looking inward for local symbols to define and add meaning to life. During the occupation, they looked towards the peasantry; Jean-Price Mars serves as the foremost resource for this pivot. Also, Sean Mills describes how this resulted in close, intimate ties between Haïti and French Canada—with the clergy in particular. Yet, many like Jacques-Nicolas Léger sought deepening ties to the US as an alternative. I expand on the shift in the later chapter regarding how Americans replaced Germans and Frenchmen as the foreign other after the occupation begins. Note that Léger and many complicit elites found profitable positions parasiting from the administrative bureaucracy inherent to the occupation. Many were also tired of the drama of the previous revolutions.

[9] Mask of Hypocrisy Dissertation

[10] As Hambelton goes on to note, many of the reports were based on or directly quoted Roger Farnham, Vice-President of City National Bank of New so thus major shareholder of the Banque Nationale de la République d’Haïti as well as ‘guardian’ of Haitian gold by early 1915, and president of the failed Haitian National Railroad. Farnham was a close friend to Secretary Bryan and would act primarily to have the US government secure and expand his extensive financial interests in Haïti

Leave a Reply