The following list highlights some of the most important dates in Haitian history. Other significant events—such as the detailed chronology of the Haitian Revolution—have been omitted to enhance clarity. (Additionally, this timeline does not extend beyond the end of the Duvalierist regime.) The references provided at the end of this page should be consulted for a more comprehensive analysis of the dates presented.

SAINT-DOMINGUE/HAITI CHRONOLOGY

1492-1500: European arrival on Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), an island inhabited by the Taíno, an Arawak-speaking population

1492-1560s: Steady decline of the Taíno population, with an estimated 86% of the population dying within a few decades of contact with Europeans. The original population is estimated to have ranged from about 1 million to 3.77 million in 1492, dwindling to only a few dozen by the 1560s.

1502: Introduction of first African slaves

1502: Death of Taino Arawak Cacique (chief) Anacaona

1521: First slave revolt in the New World (in modern Dominican Republic)

1600s: Rise of French Flibustiers culture on Spanish territory

1642: Louis XIII makes slavery legal in French colonies and possessions

1664: French West Indian Company administers island of Tortuga

1685: France issues the Édit de mars 1685, later known as the Code Noir

1697: The Treaty of Ryswick, in which Spain cedes one-third of the western shore of Hispaniola to France, forming Saint-Domingue (now Haiti)

1724-1803: French government directly administers Saint-Domingue as its colony

1743: Birth on the Bréda plantation of the future revolutionary figure Toussaint Louverture

1749: Port-au-Prince new capital of Saint-Domingue (instead of Cap-Français)

1757: “Makandal Conspiracy” led by François Makandal against slave-owners

1758 (March): François Makandal executed at Le Cap; slaves forced to watch him burnt at the stake

1770s: Gens de Couleurs Libres’ (Free Coloureds) mobility increasingly restricted in and out of Saint-Domingue

1777: Free Coloureds no longer able to enter mainland France

1178: Interracial unions outlawed in France

1779: French troops (including inhabitants of Saint-Domingue) participate in Battle of Savannah in soon-to-be United States of America

1785-1790: Peak of colonial era; approximately 30, 000 African slaves imported each year to Saint-Domingue (slave population of about 500, 000 by outbreak of uprising)

1789: Beginning of the French Revolution; hostilities explode in Saint-Domingue between (and among) whites and the gens de couleurs

1791 (21August): Bois-Caiman Vodou Ceremony?

1791 (22 August): Slave uprising begins (first in the North)

1793: Gradual abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue via French commissioners Sonthonax and Polverel

1794 (4 February): Abolition of slavery by National Convention on all French possessions

1794-1801: Toussaint Louverture rise to power in Saint-Domingue

1795: Treaty of Basel – Spain cedes Santo-Domingo (modern day Dominican Republic) to France

1800: War between Toussaint Louverture and mulatto forces led by André Rigaud

1801 (January): Louverture campaigns to Santo-Domingo (now part of the French Empire)

1801 (July): First “Haitian” Constitution written by Louverture and his secretaries

1801 (October): Moïse rebellion against Louverture

1801 ( 29 November): Execution of Moïse and other conspirers

1801-1809: American embargo on Saint-Domingue/Haiti; clandestine commerce between Northern merchants and Saint-Domingue/Haiti continues

1802 (February): Leclerc expedition

1803 (18 November): French capitulation at Battle of Vertières

1804 (1 January): Proclamation of Haitian Independence; Jean-Jacques Dessalines becomes first leader

1806 (October): Assassination of Dessalines

1807-1820: Henri Christophe succeeds Dessalines

1807/11-1820: Haiti secedes between kingdom in the North (governed by Henri Christophe) and Republic in the South/West (presided by Alexandre Pétion)

1811: Henri Christophe crowns himself Henri 1er; governs the North of Haiti as King until suicide in 1820

1807-1818: Alexandre Pétion president of South/West Haiti until death in 1818

1818-1843: Jean-Pierre Boyer accedes to presidency following death of Pétion

1820: Boyer reunites the two Haitis following Henri Christophe’s suicide

1822: Unification of Hispaniola under Haitian leader Boyer, incorporating both Haiti and the Dominican Republic

1825: Haiti agrees to an indemnity of 150 million francs to France for recognition of its independence, with settlements based on 1789 values; the debt proved nearly impossible for the newly founded nation to repay

1826: Boyer’s (particularly unpopular) Rural Code

1838: Indemnity to France was reduced to 90 million, while advantageous tariffs for French commerce were maintained

1843: “Liberal” Revolt against Boyer

1844: Dominican Republic declares independence from Haiti (and in1864 from Spain)

1844: Piquet Rebellion

1844-1915: With few notable exceptions, beginning of a period of political instability

1849-1859: Faustin Soulouque becomes president and crowns himself emperor of Haiti

1860: Concordat with the Vatican; Haiti recognized by the Holy See and attributed first archbishop in 1863

1862: United States recognition of Haitian independence

1869: Ebenezer Don Carlos Bassett appointed minister to Haiti, becomes first African American to hold such diplomatic position

1874 (November): African American James Theodore Holly ordained first bishop of Haitian Episcopal Church

1875: Haitian recognition of Dominican independence

1879-1888: Presidency of Lysius Salomon

1880: Contract signed in Paris between the Société Générale de Crédit Industriel et Commercial and Charles Laforesterie (the Haitian Minister of Finance) for the creation of the Banque Nationale d’Haïti

1889-1891: African American former abolitionist and public figure Frederick Douglass serves as minister to Haiti

1885: Haitian intellectual and politician Anténor Firmin publishes De l’égalité des races humaines to rebute Arthur de Gobineau’s pseudoscientific Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines

1891: U.S. efforts to pressure the Haitian government into ceding Môle Saint-Nicholas proved unsuccessful but served as a “useful” tool for diplomatic negotiations

1890s-1915: A period marked by extreme political instability, weakened sovereignty, a decline in Haitian-owned businesses, heightened social stratification, and the intensification of the “color question”

1890s-1910s: Increase in American imperialist activities in Latin America (and in the Pacific)

1910: Reorganization of the Banque Nationale d’Haïti into the Banque de la République d’Haïti, shifting its influence from predominantly Franco-German to American control

1914: Opening of the Panama Canal

1915 (28 July): Beginning of U.S. Marine Occupation of Haiti (formally until 1934)

1915 (September): Signing of the Haitian-American Treaty, establishing Haiti’s subordination to the United States

1916-1924: (First) U.S. Marine Occupation of the Dominican Republic

1917-1920: Cacos Wars against U.S. Marine occupation forces; wars waged in different phases

1919: Death of cacos leader Charlemagne Peralte; his body was photographed and publicly displayed to deter further resistance

1920 (1 January): Haiti joins the League of Nations (founding member until 1942)

1920s: Emergence of the Haitian Indigéniste movement

1920s: Haitian army (Garde Nationale d’Haïti and later the Force Armée d’Haïti) modernized with American military techniques

1920 (March-May): African-American field secretary of the N.A.A.C.P. James Weldon Johnson in Haiti to investigate Marine presence

1927: Haitian journal La revue indigène co-founded by Jacques Roumain and Émile Roumer

1928: Haitian intellectual Jean Price-Mars publishes Ainsi parla l’Oncle, delivering a sharp critique of the Haitian elite for its lack of social relevance; the book, later reinterpreted, becomes foundational for the emerging Noiriste movement

1930s: “Color question” intensify further; Marine occupation seen as an humiliation

1930s: Noirisme movement “grows out” of Indigénisme

1932: Jacques Roumain and Christian Beaulieu travel to New York city in hopes of securing financial support from the Communist Party of the United States to create a Communist Party in Haiti

1934: Creation of the feminist organ La Ligue Feminine d’Action Sociale (LFAS)

1934: Creation of the Haitian Communist Party with members such as Jacques Roumain

1934 (15 August): Official departure of U.S. Marines; U.S. continues to hold control of the Banque de la République d’Haïti

1937 (October): The Parsley Massacre, in which an estimated 9,000 to 12,000 individuals identified as ‘Haitians’ living in the Dominican Republic were killed

1941-2: The anti-superstition campaign, largely targeting Vodou, led by the Haitian Catholic Church, reportedly with the support of President Élie Lescot

1941: Dr Pierre Mabille acts as French cultural attaché to Haiti and becomes influential among young Marxist intellectuals in the capital

1941: Price-Mars and collaborators lunch the Institut d’Ethnologie

1944: Aimé Césaire visits Haiti

1945: Haiti joins the United Nations; Émile Saint-Lot named ambassador

1945: Noirist Daniel Fignolé and students form the Mouvement Ouvrier Paysan (MOP)

1945 (December): French Surrealist poet and writer André Breton visits Haiti at the invitation of Pierre Mabille to give a series of lectures; during his stay, he witnesses the “January Revolution” or the “Cinq glorieuses” of 1946

1945 (7 December): Young (mostly Marxist) Haitian radicals in Port-au-Prince re-lunch the journal La Ruche; editorial board includes René Depestre, Jacques Stéphen Alexis and Gérard Chenet

1946 (11 January): Lescot ousted; “Revolution of 1946”

1946 (January-August): Haitian Gardes form the CEM (Conseil Exécutif Militaire) and rule in the absence of a president

1946 (8 April): The United States recognizes the CEM

1946: Election of Dumarsais Estimé; victory of Noirisme movement

1947: Haiti regains control of the Banque de la République d’Haïti

1948 ( 30 April): Creation of the Organization of American States

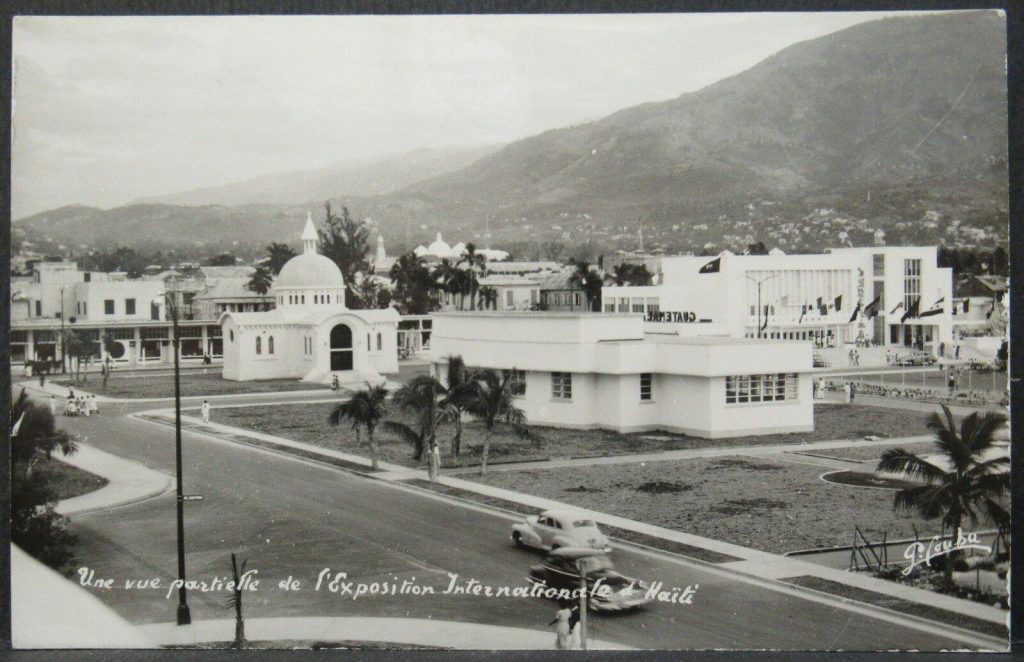

1949-1950: Estimé’s lunches lavish Exposition internationale du bicentenaire de Port-au-Prince

1950 (10 May): Coup against Estimé led by military generals including Paul Eugène Magloire

1950-1956: Presidency of Paul Eugène Magloire

1956 (September): First international Congrès des écrivains et artistes noirs held in Paris; Haiti’s Jean Price-Mars serves as president, with René Depestre and Jacques Stéphen Alexis among the attendees

1956 (December): Ousting of Paul Eugène Magloire

1956-1957: Period of political instability; Joseph Nemours Pierre-Louis, Franck Sylvain, Léon Cantave, Léon Cantave, Daniel Fignolé and Antonio Thrasybule Kébreau all “elected” presidents for short moments

1957 (22 September): François Duvalier “elected” president

1957-1986: Duvalier Dictatorship

1958: Creation of violent paramilitary force Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale (VSN) known as the Tontons Macoutes following coup attempt against François Duvalier

1959 (30 December): Creation of the Inter-American Development Ban

1960: Upper-class Haitians gradually leave Haiti to flee Duvalier’s dictatorship

1961: Jacques Stephen Alexis leads a failed Communist coup against Duvalier; he is subsequently tortured and murdered

1962: François Duvalier’s Rural Code

1963 (September): First reported Haitian “boat people” arrive to South Florida and demand political asylum

1964: François Duvalier named president for life

1971: Death of François Duvalier

1971-1986: Jean-Claude Duvalier succeeds his father and continues dictatorship

1980: Jean-Claude Duvalier marries Michèle Bennett, a “light-skinned” member of the elite “mulatto” circles; this alliance prompts a reconsideration of François Duvalier’s Noiriste ideology

1982: Jean-Bertrand Aristide, then an ordinary priest, delivers sermons in which he openly criticizes the atrocities of the Duvalier dictatorship

1984: Food riots soon turn into political riot

1985 ( 27 November): Three students are killed in Gonaïves, sparking major demonstrations across the country, with anger directed at the Duvalier government

1986 (7 February): Jean-Claude Duvalier flees Haiti for France with an estimated $120 million, marking the end of the Duvalier dictatorship. Military factions and neo-Duvalierist groups seize power, ushering in a period of political confusion and the failure of a democratic transition

➠ Please do not copy this list without permission from administration. Use for educational purposes only.

♦ ♦ ♦

References:

Monographs and Articles

Fick, Carolyn E. The Making of Haiti: The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below. Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1990.

Fischer, Sibylle. Modernity Disavowed: Haiti and the Cultures of Slavery in the Age of Revolution. Duke University Press, 2004.

Frostin, Charles. Les révoltes blanches à Saint-Domingue aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Haïti avant 1789). Ecole, 1975.

Geggus, David Patrick. Haitian Revolutionary Studies. Indiana University Press, 2002.

Hoffmann, Léon-François. Histoire littéraire de la francophonie: littérature d’Haïti. Chicoutimi: J.-M. Tremblay, 2013. http://classiques.uqac.ca/contemporains/hoffmann_leon_francois/litterature_dHaiti/litterature_dHaiti.html.

———. “Les Etats-Unis et les Américains dans les lettres haïtiennes.” Études littéraires 13, no. 2 (1980): 289.

James, C. L. R. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. Penguin Books Limited, 2001.

Landers, Jane, and Barry Robinson. Slaves, Subjects, and Subversives: Blacks in Colonial Latin America. UNM Press, 2006.

Leyburn, James G. The Haitian People. Yale University Press, 1948.

Oliver, Jose R. Caciques and Cemi Idols: The Web Spun by Taino Rulers Between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. University of Alabama Press, 2009.

Smith, Matthew J. Red and Black in Haiti: Radicalism, Conflict, and Political Change, 1934-1957: Radicalism, Conflict, and Political Change, 1934-1957. University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Sprague, Jeb. Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in Haiti. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012.

Stone, Erin Woodruff. “America’s First Slave Revolt: Indians and African Slaves in Española, 1500–1534.” Ethnohistory 60, no. 2 (March 20, 2013): 195–217.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Haiti, State Against Nation: The Origins and Legacy of Duvalierism. Monthly Review Press, 1990.

Wilson, Samuel M. Hispaniola: Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Web Pages

Haiti-Reference. “Calendrier Fêtes.” Accessed October 26, 2014. http://www.haiti-reference.com/histoire/calendrier-fetes.php.

Perspective Monde. “Haïti: Chronologie depuis 1945.” Accessed October 26, 2014. http://perspective.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/servlet/BMHistoriquePays?codePays=HTI&langue=fr.